VEST’S TIME OF TRUTH

By STEPHEN BLATCHFORD

SOURCE: GOAL Article September 1980

The moors around Barnsley in West Yorkshire are hard and granitic, bleak and raw in winter and hardly softened by the summer winds that sweep the Pennine tops. Down in the dales, men sweat and drive deep into the forbidding rock for the coal that brings a measure of prosperity to tiny communities huddled along the sides of the hills and the valley floors.

Hard lives are made grimmer by the slag heaps, the mining residues that bury the thin green grass or coat it with a film of dust floating off the slag and reducing everything it covers to a miserable granite-grey. It’s a hard life and a hard country, and it breeds a hard-seeming people. Even the names of the villages around Barnsley have a flinty ring — Brierly, Grimethorpe. But there’s warmth, comfort and cheer in the people of the dales. They get together in groups for their recreation and entertainment —brass bands, choirs and football, the inevitable football. Football in these hills means Soccer. North and west they may play Rugby League or even Union — but around Barnsley it’s Soccer. Out of Grimethorpe and these hills came “Soccer Draft”, the book that started Michael Parkinson on his way to emancipation from the shackles and the hardships of a mining community and to television stardom.

Out of these hills came Tommy Taylor, transferred from Barnsley to Manchester United for £29,999 just so he would not become the first £30,000 player in British football history. Matt Busby had no wish to weigh down the soaring career of such a fine striker with a £30,000 tag. (But two years later Taylor was dead, crushed in the horrific Munich air crash that smashed the greatest club team England has known and stopped a nation in its tracks.)

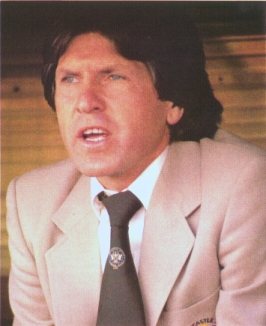

And out of these grey valleys came Newcastle United manager Alan Vest, shrewd, pragmatic dry of wit and humour — and as soccer-daft as Parkinson. From the tiny village of Brierly he went to school at Hemsworth Grammar, where he played Rugby Union —‘because there was nowt else.” Outside school he played Soccer with Garfield Road Juniors. He had a spell with Leeds United as an amateur, but “They didn’t seem to anxious to sign me up. And anyway, it had always been Barnsley for me. Barnsley played some great Soccer under Tim Ward, and people outside the West Riding were beginning to realise it.” People were. My newspaper sent me up from London to do a series of articles with Ward, who had made his name as a skilful and intelligent wing half playing alongside such immortals as Raich Carter, Peter Doherty, Daily Duncan. Frank Broome and Leon Leuty at Derby County, and who was proving just as deep-thinking and skilful as a manager at Barnsley.

Vest’s Soccer philosophy shows much of the influence of Ward. Like Ward a lover of the skills and artistry of the game, Vest, again like Ward, came quickly to terms with the realities of the situation he was in as a manager. He developed styles and methods of play dictated by the abilities of the players he has and those he can afford to buy. Realising that his big, strong central defenders were fine for breaking up opposition attacks but lacking the skills to play the ball out of defence, he based his style on the long, strong clearance, by-passing his midfield whose job it is to back up the strikers and get back quickly to form the first line of defence as soon as Newcastle’s attacks break down. His fullbacks, too, rely mainly on the long ball to clear their lines, although both Col Curran and Paul Reaney are fine attacking players when spaces are created down the flanks. It is a simple and effective method, but it depends on the scoring ability of the front-runners, and that is where Newcastle falls down. There is an acute shortage of scoring power all over Australia. Obsessed with the need for ball skills, coaches develop strikers capable of taking on defenders and weaving delicate patterns on the way to goal. Central strikers who can score goals but have little ball artistry are rejected in favour of players with brilliant close skills but little ability to finish. Vest showed his appreciation of his problem at Newcastle by naming one player — John Kosmina of West Adelaide. “Now that’s a player I’d like if he was available. But there isn’t enough money in Newcastle to buy him.”

And that led Vest to another topic. He asked me if transfer fees were going to keep rising, then said: “Yes, I suppose they are. But it’s getting out of hand. They’re way too high already. People are talking about Gary Cole being under priced at $100,000 —that’s the price AEK of Greece is supposed to have offered for him. “I’ve seen it reported that he would be worth twice that if he was playing in Europe. But we can’t compare ourselves with Europe. We’ve got to come down to earth and realise that we are just part-timers, and that none of our players is worth that kind of money.” This is from the man who got the highest internal transfer fee in Australian Soccer history $30,000 in cash and player value for Kenny Boden. “I’ve cost Newcastle United an average of $11,000 a year for players in the three seasons I’ve been here,” Vest says. “And that includes building the first team from scratch in 1978. I spent a bit this year but it cost them nothing because I made a bit as well.” Vest is referring to the signing of former Leeds and England fullback Paul Reaney and the transfer deal which took Kenny Boden from Newcastle to Sydney City for $25,000 plus Mark Trenter. Vest has since sold Trenter back to Sydney City for more cash to boost Newcastle’s meagre coffers.

Newcastle have achieved remarkable results in their two-and-a-half years in the Philips League. Without a ground of their own or a licensed club to support them, they’ve managed to hold a respectable position in the league, produce some of the finest young players in Australia, and draw the biggest home attendances in the country. And the two men most responsible for those achievements have been Vest and secretary Paul Trisley, whose shrewd and capable administration has been the ideal accompaniment to Vest’s managerial acumen. Vest has one priceless asset at Newcastle which few other club managers in Australia have, despite their protestations — complete and unquestioned authority for all team affairs. It’s a wise and rare board or committee that finds the right man and then leaves him alone to get on with the job. Vest makes the most of this without abusing it. ‘He buys good players cheaply. If there aren’t any available, he doesn’t buy.

He shrugs off criticism that he should develop the immense pool of local talent rather than importing players of limited ability and future. “That’s easy to say, but you can’t pack a Philips League side with teenagers, however talented they are, and expect them to get results,” he says. “You’ve got to have a solid basis of players with experience and character to pull the young ‘uns through when the going gets tough. And it often does get tough in the Philips League.” To buy the players he needs and can afford Vest goes back to England in the close season and confers with his friends and associates of past years in clubs in many parts of the country. That’s ‘how he got players like Boden and Bill Summerscales to help launch Newcastle in the Philips League. And that’s how he was able to sign Reaney on a two year contract for the start of the 1980 season. “You’ve got to be there, on the spot, to know who’s available or likely to be,” Vest says. “It isn’t something you can do by remote control or at the end of a 20,000-kilometre telephone line.”

Vest goes back to New Zealand, too, for players likely to keep up the strength at Newcastle. That’s where he went at the end of June, to the country where he served as player-manager of Gisborne City for three years and then for a year with New Brighton, the Christchurch club. The connections he made in New Zealand from 1971 to 1974 enabled him to sign Roy Drinkwater and Phil Dando for Newcastle’s entry to the Philips League. “And they’ve been worth their weight in dollar notes to us,” he says. “Apart from playing their hearts out every week, the older players have helped the young fellows along, steadying them down when things go wrong or when they get the bit between their teeth and get a bit headstrong. “It takes a while to develop judgment and character in young fellows as well as football ability. You can’t make a good wine or even a good cheese overnight. You’ve got to give them time to mature. Why should it be any easier with human beings?”

Vest is concerned for the future of Newcastle: “There’s tremendous support in the area for the club, but they want to see a bit of success. Without a licensed club and a ground of our own, I don’t see how we can give them success. And there’s only so much I can do. Any manager has got only so many ideas. “After three or four years, either the manager should be changed or the environment. “People like Matt Busby, Scott Duncan, Don Revie, Malcolm Allison, Bobby Robson, Terry Venables, Alan Mullery, Brian Clough, Lawrie McMenemy and Bill Shankly had a fund of ideas. They were able to build up Manchester United, Leeds, lpswich, Crystal Palace, Brighton, Nottingham Forest and Liverpool because they had ideas. “But they also had the resources. It all comes back to money. You’ve got to have money to buy players or to develop amenities at the ground. “Either way you bring the spectators in. Then when they come in, you’ve got the money to go on developing your ideas. You can only go so far with ideas alone. “There’s only so much you can do without money. After that you begin to repeat yourself. Then you begin to bore people. When you do that, it’s time for a change. Either you change the manager or you change the environment.”

Does that mean his days at Newcastle are numbered? “I don’t know. I really don’t know. I like it at Newcastle. The city and the club have been good to me. I think we’ve done a good job there. “But without money, there isn’t much more I can do. There isn’t much more anybody can do. “Our sponsors have been good to us. They’ve upped the ante for next year. But it’s still not enough without a licensed club and a ground of our own. “This is a great club. The directors, the members, the supporters and the team are great people. I’m left alone to do the job as I see it. And I’ve got a home in Nelson Bay, which must be one of the nicest places to live anywhere in the world. “And I’ve got a great coach and assistant — Frank Campbell. He’s a truly funny lad, and a sense of humour like his is absolute magic in our situation where we’re trying to make bricks without much straw. “I even have to scrounge around for pitches to train and practice on. “I’d like to stay on at Newcastle. But I don’t know there’s much more I can do for them. If they can’t change the environment — get more sponsorship, a licenced club, their own ground or something — then maybe they would be better off getting a new manager.”

Vest and Campbell are the same sort of partnership as Clough and Peter Taylor, Revie and Syd Owen, Terry Neill and Don Howe. One is the thinker, the other the doer. One does the planning, the other puts it into practice. One makes the decisions, the other carries them out. “But I get out with the lads a lot more than Neill or Clough or Revie,” says Vest. “I have to. We can’t afford a team of coaches to work with Frank while I sit in the office. I have to get out there in my tracksuit and do my bit.”

Vest has never been able to sit in the office and let somebody else do the real work since he became a player-manager with Rugby Town in 1969. After leaving Barnsley to join Peterborough United in 1961, Vest went to King’s Lynn and Boston United before moving to Rugby — where that other game is mythically reputed to have started with a weirdo called Webb-Ellis. Vest had his full FA coach’s badge when he arrived at Rugby, and had been working as a staff coach on preliminary badge courses and at residential coaching courses for the England Schoolboys’ squad. Under his guidance Rugby won the Southern League, then in 1971 he moved to New Zealand. He kept Gisborne City, a club in a town of only 25,000 people, in the top four of the national league for three years, then moved to Christchurch to lift New Brighton from second last to second in one year — while Gisborne slid out of the league.

In 1974, Vest left New Zealand to become director of coaching in Western Australia. He also took the State coach’s job, and twice won an international tournament in Indonesia, beating the South Korean national team in the final both years. “In that time we also beat Glasgow Rangers, drew with Middlesbrough and lost 2-1 to Manchester United after missing a penalty,” he says. He doesn’t say that he also helped to develop players like David Jones and Gary Marocchi, both now with Adelaide City and Australian internationals, and Arno Bertogna, another Socceroo now with Newcastle United.

In 1976 he went to England to join Brian Green at Rochdale, after Green’s brief spell as Australia’s national coach. “We had Rochdale at the top of the table until Christmas,” Vest says. “Then the club got rid of several of our best players to raise some money and we finished the season in the middle of the table.” The next year Green went to Leeds as coach, and Vest came back to Australia to take over from Mike Laing at Western Suburbs. Before he left for England to join Rochdale, Vest came near to succeeding Green as national coach. He was on a short list of four with former national coach Rale Rasic, former Australian Soccer idol Johnny Warren, and the man who stunned almost everybody in Australia by getting the job — Jimmy Shoulder. Vest says: “When I think about it now, Rale should have got the job, but it’s clear that he’s offended somebody at the top and I don’t think he’ll ever get the job.”

Vest thinks the job should go to someone who has experience of Australian Soccer and the conditions, limitations and players he’ll have to work with. “And I certainly don’t think we should be playing men who haven’t yet qualified as Australians, particularly when they’ve got a limited future. “I’ve got nothing against Ivo Prskalo or Jim Muir, but they’ve only got a few more years left, if that. We ought to be persevering with younger players —Arno Bertogna, Peter Tredinnick. Prskalo and Muir can’t get any better. The younger players can only get better. They have time on their side, but they must be given the opportunity.” But how does this square with Vest’s defence of his own policy of maintaining a solid basis of older more experienced players, keeping younger men out of the team? “We haven’t kept younger players out of the team. We’ve taken our time, blooding them gradually. We’ve got Bertogna, McClelland, Tredinnick and Cowburn who are regular members of the team. They’re all under 21. “How many Philips League sides can match that?

But the point is that before you can put them in the team, you have to have them in the squad. Instead of gradually seasoning players like Bertogna in the national team, the plan seems to be to turn brilliant midfielders into sweepers and stoppers. It doesn’t make sense to me.” Vest went to Rochdale because he felt he could learn something by working with Green, who had been Coach of the Year in England before coming to Australia. And Vest came back to Australia when Green went to Leeds because he wanted to take over a Philips League club. “But Mike Laing hung on at Wests, so I took the job as director of coaching in Northern NSW,” Vest said. Even then he had his eye on managership of the club being formed to make late entry into the Philips League.

It duly came to pass, and Vest set out to make a first-class team on a shoestring. If Newcastle hasn’t set the world alight, Vest has certainly made his contribution to Australian Soccer: Boden, Bertogna and Joe Senkalski to the national team, Peter Tredinnick, Malcolm McClelland and Michael Boogard to the youth team, Tredinnick on the fringe of the national squad and younger brother Howard Tredinnick in line for a place in the 1981 youth squad. It’s not a bad record, specially for a man who is sometimes accused of not giving adequate chances to young players. And in defence of Newcastle’s disappointing record at the half-way stage of this season, Vest points out that the team has been upset by a string of injuries. “This season we’ve had Drinkwater, Summerscales, Bertogna, Cowburn, Jim Preston and McClelland injured. We’ve been without Senkalski for months because of injuries he got playing for Australia. “And we don’t have the reserve strength that most Philips League clubs can draw on. We just can’t afford it.”

As Vest says, it all comes back to money. And few know better how to get along on a meagre budget than a man from the mining valleys of the West Riding. There, they have two sayings. “Where there’s muck there’s money” and: “Hear all, see all, say nowt, “Drink all, sup all, say nowt, “And if ever tha’ does owt for nowt, “Allus do it for tha’ sen.” But if Vest followed those precepts, Newcastle would be a poorer place.